Human Rights Watch, March 22, 2010 -

(New York) – Google’s decision to stop censoring its Chinese search engine is a strong step in favor of freedom of expression and information, and an indictment of the Chinese government’s insistence on censorship of the internet, Human Rights Watch said today. Google announced today that it would not censor searches and instead redirect searches to its uncensored Hong Kong-based site that would provide results in simplified Chinese. The company also said it would monitor and publicize any attempts at censorship of the site by the Chinese government.

“China is one of the world’s largest economies, but hundreds of millions of Chinese internet users are denied the basic access to information that people around the world take for granted,” said Arvind Ganesan, business and human rights director at Human Rights Watch. “Google’s decision to offer an uncensored search engine is an important step to challenge the Chinese government’s use of censorship to maintain its control over its citizens.”

China’s estimated 338 million internet users remain subject to the arbitrary dictates of state censorship. More than a dozen government agencies are involved in implementing a host of laws, regulations, policy guidelines, and other legal tools to try to keep information and ideas from the Chinese people. Various companies, including Google, Yahoo!, and Microsoft, have enabled this system by blocking terms they believe the Chinese government will want them to censor. Human Rights Watch documented this corporate complicity in internet censorship in China in “Race to the Bottom,” a 149-page report published in August 2006.

On January 12, 2010, Google announced that it was prepared to withdraw from China unless it could operate its Chinese search engine, Google.cn, free of censorship. This decision was made after the company disclosed “highly sophisticated and targeted attacks” on dozens of Gmail users who are advocates of human rights in China. Google said some 20 other companies were also targets of cyber attacks from China. On February 18, 2010, the New York Times reported that these attacks had been traced to Shanghai’s Jiaotong University and the Lanxiang Vocational School. The latter reportedly has close ties to the Chinese military.

In response to the prospect that Google might stop censoring its search engine, on March 12, Li Yizhong, China’s minister of industry and information technology, said, “If you want to do something that disobeys Chinese law and regulations, you are unfriendly, you are irresponsible and you will have to bear the consequences.”

On January 22, 2010, in a major speech on internet freedom, US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton called on the Chinese government to investigate those attacks. She also noted that the “private sector has a shared responsibility to help safeguard free expression. And when their business dealings threaten to undermine this freedom, they need to consider what’s right, not simply the prospect of quick profits.”

Human Rights Watch said that companies operating in China or other countries have an obligation to safeguard freedom of expression and privacy online. The Global Network Initiative (GNI), an international effort comprised of companies, including Google, Microsoft, and Yahoo!, human rights organizations such as Human Rights Watch, academics, and socially responsible investors to protect freedom of expression and privacy online, recommends that companies: “challenge the government in domestic courts or seek the assistance of relevant government authorities, international human rights bodies or non-governmental organizations when faced with a government restriction that appears inconsistent with domestic law or procedures or international human rights laws and standards on freedom of expression.”

Human Rights Watch called on other companies to follow Google’s example and end all their censorship of politically sensitive information.

“This is a crucial moment for freedom of expression in China, and the onus is now on other major technology companies to take a firm stand against censorship,” said Ganesan. “But the Chinese government should also realize that its repression only isolates its internet users from the rest of the world – and the long-term harm of isolation far outweighs the short-term benefit of forcing companies to leave.”

- Human Rights Watch

![[googleCN]](http://si.wsj.net/public/resources/images/OB-HX710_google_G_20100322172337.jpg)

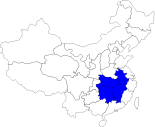

THE CROSSROADS

THE CROSSROADS All of the dynamics driving the first four nations converge in the Crossroads. The middle stretch of the Yangtze is a natural transportation and communications nexus. It is the heart of China, pumping the lifeblood of men and material to every other part along capillaries of water, road, and rail. Interrupt this heartbeat—as a freak snowstorm did last year when it hit the Crossroads during Lunar New Year—and the entire country can grind to a halt. But the region’s central strategic position has never translated into political power. Instead, it has always been a zone of competition among its stronger neighbors, a place for their rival armies to march and fight.

All of the dynamics driving the first four nations converge in the Crossroads. The middle stretch of the Yangtze is a natural transportation and communications nexus. It is the heart of China, pumping the lifeblood of men and material to every other part along capillaries of water, road, and rail. Interrupt this heartbeat—as a freak snowstorm did last year when it hit the Crossroads during Lunar New Year—and the entire country can grind to a halt. But the region’s central strategic position has never translated into political power. Instead, it has always been a zone of competition among its stronger neighbors, a place for their rival armies to march and fight. The wetlands along the Yangtze and its tributaries supply much of China’s rice, fish and fowl, and the surrounding hills are rich in orchards above ground and minerals below. But nearly all of its resources—the electricity generated by the Three Gorge Dam, the copper mined to make electrical wiring—flow outward to fuel China’s more developed coastal provinces. The most important outflow is human. Along with the Refuge, the Crossroads supplies the vast majority of China’s migrant workers, a floating population of 150 million people.

The wetlands along the Yangtze and its tributaries supply much of China’s rice, fish and fowl, and the surrounding hills are rich in orchards above ground and minerals below. But nearly all of its resources—the electricity generated by the Three Gorge Dam, the copper mined to make electrical wiring—flow outward to fuel China’s more developed coastal provinces. The most important outflow is human. Along with the Refuge, the Crossroads supplies the vast majority of China’s migrant workers, a floating population of 150 million people. Standing in the crosscurrents of so many comings and goings, the Crossroads functions not only as China’s physical heart but as its emotional heartland as well. When migrants return home, they bring back ideas and experiences from every part of China, which mix and recirculate through the entire body. It helps that the inhabitants of Chu—as the Crossroads was called in ancient times—have long been known for their strong passions and fierce loyalties. It is no coincidence that the popular uprisings that began both the Nationalist and Communist revolutions happened here, or that many of China’s leading reformists and revolutionaries, including Mao, rank among its native sons. But while many things begin in the Crossroads, few ever reach their fruition there.

Standing in the crosscurrents of so many comings and goings, the Crossroads functions not only as China’s physical heart but as its emotional heartland as well. When migrants return home, they bring back ideas and experiences from every part of China, which mix and recirculate through the entire body. It helps that the inhabitants of Chu—as the Crossroads was called in ancient times—have long been known for their strong passions and fierce loyalties. It is no coincidence that the popular uprisings that began both the Nationalist and Communist revolutions happened here, or that many of China’s leading reformists and revolutionaries, including Mao, rank among its native sons. But while many things begin in the Crossroads, few ever reach their fruition there.